Six Big Losses In Lean Manufacturing

What Are the Six Big Losses?

The Six Big Losses is the concept and practice of categorizing productivity loss from an equipment perspective. The Six Big Losses originate from the world of Total Productive Maintenance (TPM). Seiichi Nakajima developed TPM and the Six Big Losses in 1971 while at the Japanese Institute of Plant Maintenance. He characterized maintenance as the responsibility of all employees; best carried out through small group activities with the goal of maximizing equipment effectiveness.

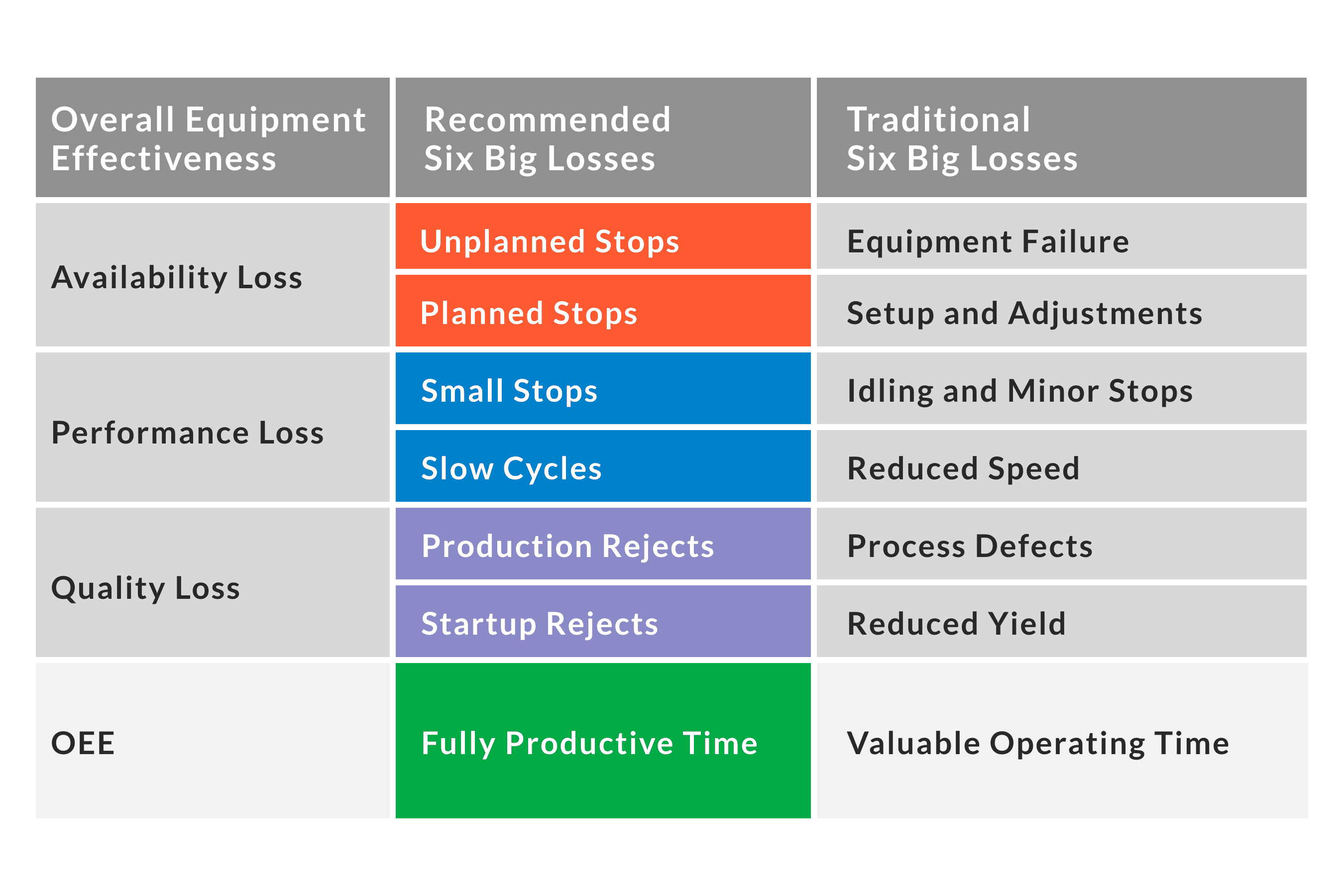

Six Big Losses align directly with OEE and provide an additional and actionable level of detail about OEE losses. The traditional Six Big Losses include Equipment Failure, Setup and Adjustments, Idling and Minor Stops, Reduced Speed, Process Defects, and Reduced Yield. We recommend a simpler and more consistent set of names to drive adoption. Our recommended names are Unplanned Stops, Planned Stops, Small Stops, Slow Cycles, Production Rejects, and Startup Rejects. Each of these relates directly to one of the three OEE factors.

Why Use the Six Big Losses?

The Six Big Losses are very well-aligned to discrete manufacturing and provide a more detailed perspective on equipment loss than OEE. Since the Six Big Losses are derived from TPM, each loss maps very well to a specific set of countermeasures. Not only do you get more information – you get a foundation for more effective actions.

The Six Big Losses in Lean Manufacturing

The Six Big Losses align with the three OEE factors, so your actions to address these losses will directly translate to a reduction in Availability Loss, Performance Loss, and Quality Loss. In turn, your OEE score will improve, indicating a more efficient manufacturing process. A focus on mitigating these losses is a great starting point for improvement.

Unplanned Stops

Unplanned Stops are significant periods of time in which equipment is scheduled for production but is not running due to an unplanned event. Examples include equipment breakdowns, tool failures, unplanned maintenance, lack of operators or materials, being starved by upstream equipment or being blocked by downstream equipment.

Planned Stops

Planned Stops are periods of time in which the equipment is scheduled for production but is not running due to a planned event. Examples include changeovers, tooling adjustments, cleaning, planned maintenance, and quality inspections. Many companies also categorize breaks and meetings as Planned Stops.

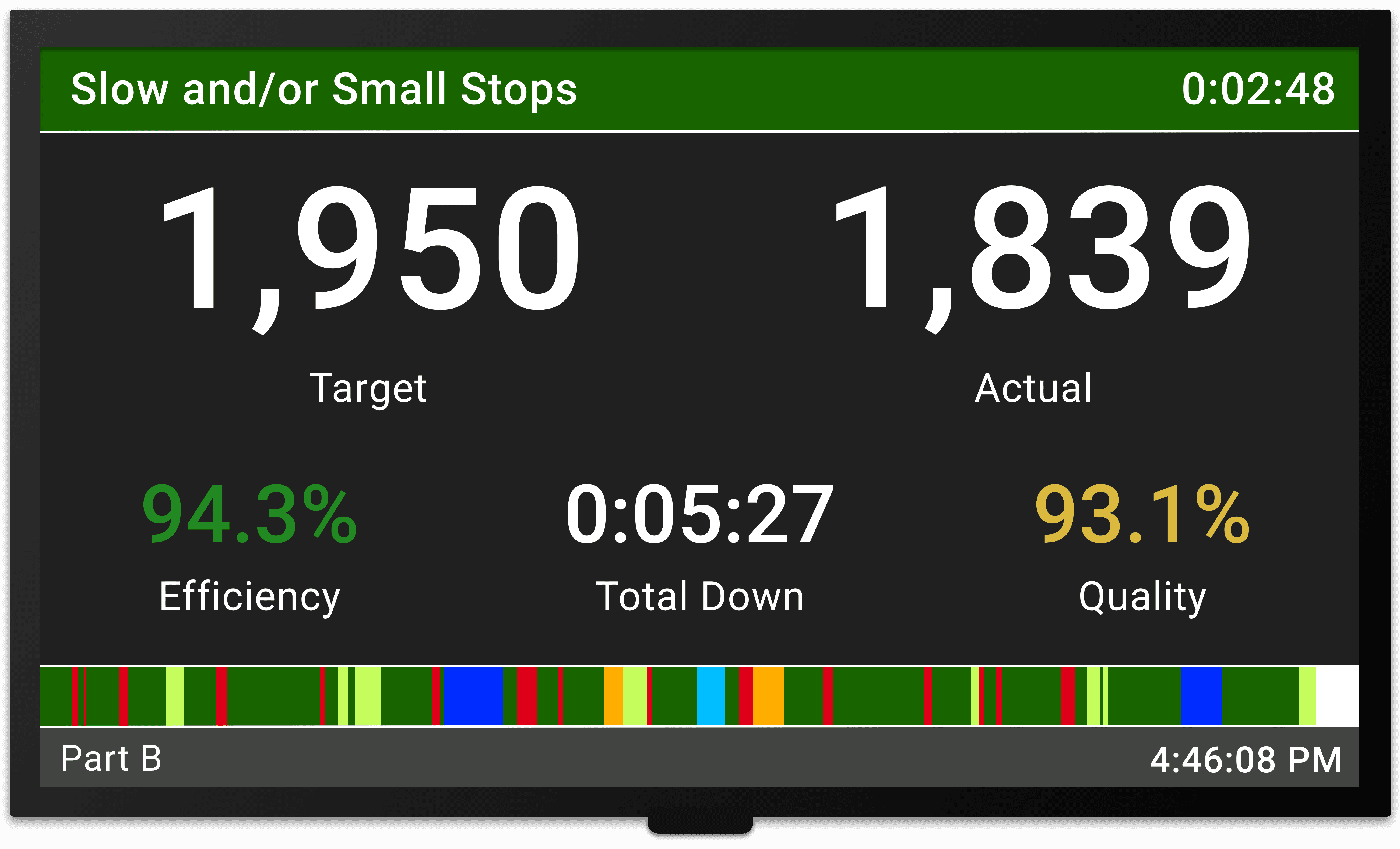

Small Stops

Small Stops occur when equipment stops for a short period of time (typically a minute or two) with the stop resolved by the operator. Small Stops are often chronic (same problem/different day), which can make operators somewhat blind to their impact. Examples include misfeeds, material jams, incorrect settings, misaligned or blocked sensors, equipment design issues, and periodic quick cleaning.

Slow Cycles

SSlow Cycles occur when equipment runs slower than the Ideal Cycle Time (the theoretical fastest possible time to manufacture one piece). Examples include dirty or worn out equipment, poor lubrication, substandard materials, poor environmental conditions, operator inexperience, startup, and shutdown.

Production Rejects

Production Rejects are defective parts produced during stable (steady-state) production. This includes parts that can be reworked, since OEE measures quality from a First Pass Yield perspective. Examples include incorrect equipment settings, operator or equipment handling errors, or lot expiration (e.g., pharmaceutical).

Startup Rejects

Startup Rejects are defective parts produced from startup until stable production is reached. They can occur after any equipment startup, however, are most commonly tracked after changeovers. Examples include suboptimal changeovers, equipment that needs “warm up” cycles, or equipment that inherently creates waste after startup (e.g., a web press).

Benefits of Utilizing Six Big Losses

In the short term, Six Big Losses provides additional information that aligns with and extends OEE (improved information).

In the long term, Six Big Losses makes it easier to identify effective countermeasures for equipment-based losses (improved actions).

Team Member Roles

Six Big Losses involves the following roles:

| Role | Description |

|---|---|

| Manager | Define how data will be collected. Define standards for determining Ideal Cycle Times. Define and maintain reason codes. Set and track improvement targets. Identify strategic improvement initiatives. Audit for sustainability. |

| Supervisor | Validate Ideal Cycle Times. Review losses at the start of each shift to identify and assign improvement actions. Audit accuracy of data capture. |

| Operator | Capture reason codes for all Unplanned and Planned Stops. Suggest improvements and actions based on observations. |

Key Insights for Six Big Losses

Monitor the Constraint

Every manufacturing process has a constraint, which is the fulcrum (i.e., point of leverage) for the entire process. Measure Six Big Losses at the constraint and focus your improvement efforts to improve the constraint. This will be the fastest path to improved throughput and profitability.

Don’t Hide Loss

Time that can be used for value-added production (i.e., manufacturing to meet customer need as opposed to manufacturing for inventory) should be used for value-added production. If it is not – that time should be categorized as a loss. This strict standard drives innovation and improvement. Every loss can be targeted and improved.

This is the reason that many companies choose to categorize breaks and meetings as Planned Stops, and are also very careful to ensure that their Ideal Cycle Times are based on the fastest possible time to manufacture one piece (not “standard” or “budget” times).

Standardize Changeover Time Measurement

Measure changeover time accurately and consistently by standardizing the measurement. It is usually measured as the time between the last good part of the prior run to the first good part of the next run. You can define your own standard – the important thing is to be consistent.

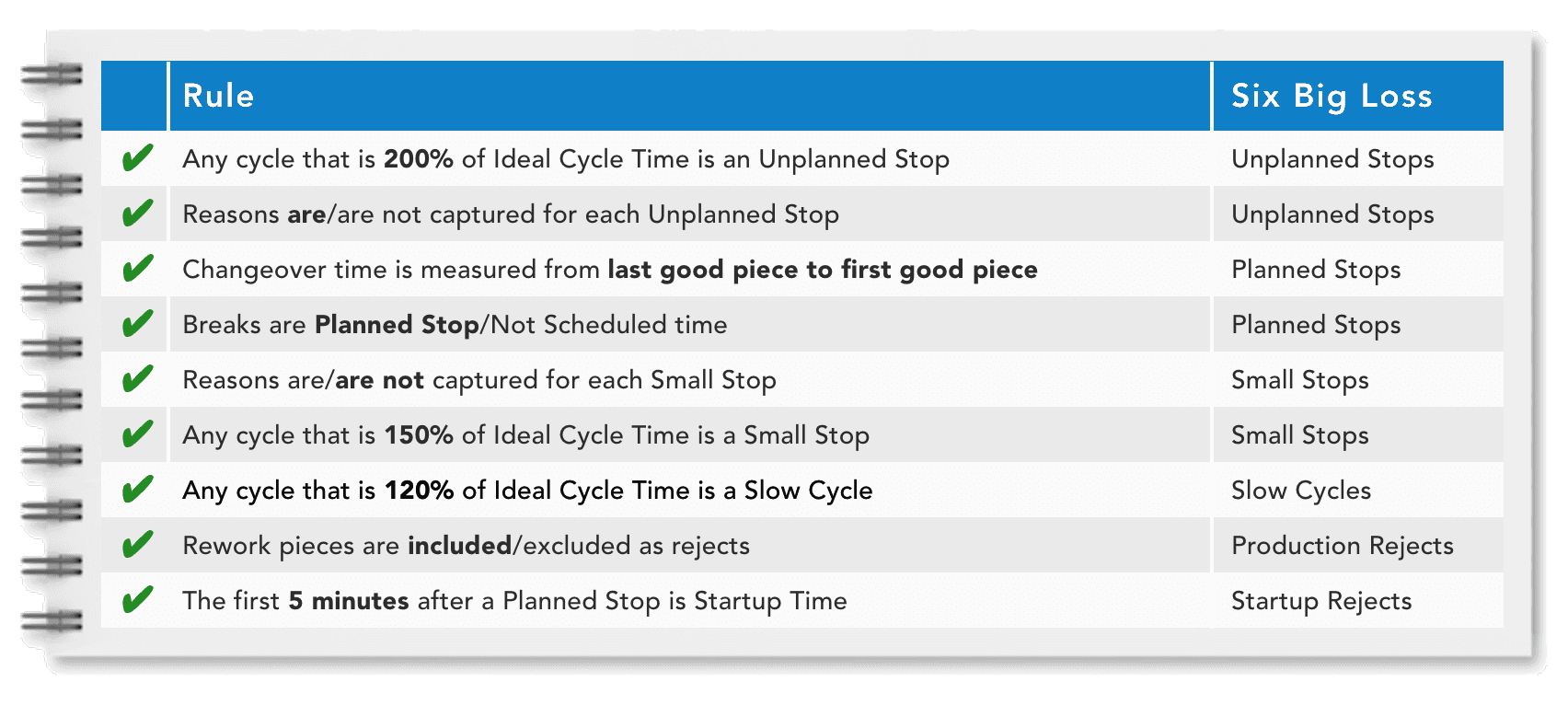

Create a Six Big Loss Rulebook

Consistency is important when using the Six Big Losses as a benchmark (comparing across shifts, equipment or plants) or as a baseline (comparing over time). Create written standards to ensure consistency.

Automate Data Capture

Automated data capture significantly improves measurement accuracy for Unplanned and Planned Stops, and is the only way to accurately measure and differentiate losses from Slow Cycles and Small Stops.

A quick rule of thumb for setting the threshold between an Unplanned Stop (OEE Availability Loss) and a Small Stop (OEE Performance Loss) is to define Unplanned Stops as long enough to require a reason to be logged – and then deciding what that duration should be.

Actions Speak Louder Than Words

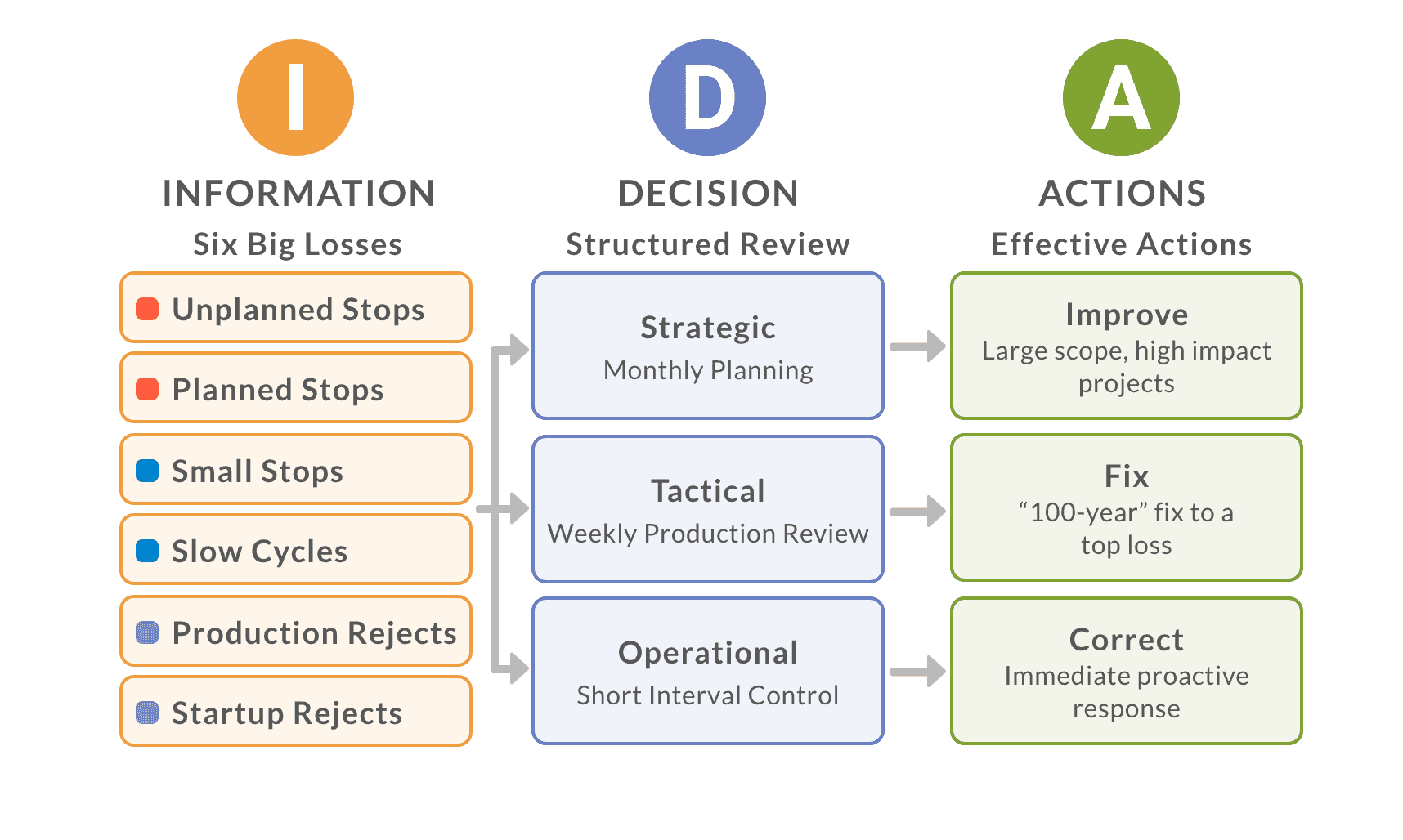

The Six Big Losses provide valuable information and insights, but most of their value comes from using that information to drive actions. An excellent framework for driving actions is the combination of IDA and Structured Improvement.

- IDA transforms information into actions through focused decision-making at all levels of the company (strategic, tactical, and operational).

- Structured Improvement ensures those actions are aligned through all levels of the company.

Level and Difficulty

The Level is Foundation. Six Big Losses are a natural extension to measuring OEE and provide valuable insights for driving improvement.

The Difficulty is Moderate. The core concepts are straightforward. However, capturing accurate and complete information requires automation (which can be easily achieved with an off-the-shelf system).

Rate Yourself on Six Big Losses

How good are you at Six Big Losses? Answer ten simple questions to see how close you are to a model implementation.

| Question | ✔ |

|---|---|

| 1. Are all six (6) of the Six Big Losses being measured? | |

| 2. Do all operators and supervisors understand the Six Big Losses? | |

| 3. Are all losses measured from the perspective of the constraint? | |

| 4. Are reasons captured for all Unplanned Stops? | |

| 5. Are changeovers, breaks, and meetings categorized as Planned Stops? | |

| 6. Are validated Ideal Cycle Times available and in use for each part? | |

| 7. Are rework parts counted as rejects (First Pass Yield perspective)? | |

| 8. Do all teams use the same Six Big Loss Rulebook? | |

| 9. Is data capture automated to improve accuracy? | |

| 10. Is a formal framework in place to transform information to actions? |

Comments or Questions?

We welcome your comments and questions. Contact us at: info@vorne.com.